A scholar’s essay on Macbeth and American Democracy

Abraham Lincoln and the Democracy of Macbeth

Angus Fletcher

It was August 1863 in America, a month after Union and Confederate forces had clashed at Gettysburg in a battle of such inconclusive slaughter—more than 50,000 maimed or buried, for no obvious result—that both sides would come to count themselves the losers. The Confederate commander, Robert E. Lee, offered his formal resignation. The Union commander, George Gordon Meade, was bemoaned by Yankee senators—and subsequently pushed aside for Ulysses S. Grant.

Meanwhile, at the White House, President Abraham Lincoln drew himself up to the low, six-legged table that he used as his daily work desk. And pulling out a much-thumbed copy of Shakespeare, he remarked: “I think nothing equals Macbeth.”

Why? Why was America’s elected leader musing about the Bard’s Scottish play? Why did he enthuse, during one of modern democracy’s darkest times, about an old script that had been penned for a middling king (England’s James I) and titled for a dreadful one?

Let’s start with the clearest and most immediate reason: to Lincoln, Macbeth served as an omen of what he could himself become. Like Lincoln, Macbeth was not just a great leader but a good one—full, in his wife’s memorable phrasing, “of the milk of human kindness.” This poetic assessment is often taught in schools as evidence of Lady Macbeth’s wickedness, an indication that she is unmaternal—and therefore deviant. But whatever it may say (or not) about Lady M, it is a striking avowal of Macbeth’s gentle heart. It reminds us that Macbeth becomes a monster not because of, but in spite of, his character. If power’s allure could warp Macbeth, the drama whispers, it can warp any of us, no matter how noble our nature.

This, we know from Lincoln’s private papers, was the warning that he personally took from Shakespeare’s play. To him, the Weird Sisters’ prediction was a glimpse not merely of Macbeth’s future but of his own. Thus it was that Lincoln believed, to his dying night, that he must remain vigilant about the morrow the Sisters had seen. For the moment he forgot the prophecy of the good soul ruined by ambition, the moment it would start to manifest in him.

Before delving further into why Lincoln’s thoughts moved after Gettysburg to his copy of Macbeth, it’s worth pausing to reflect on how extraordinary it is that an American president would fixate so intensely on the speed at which he could be corrupted by power. Certainly, there have been many presidents who have acknowledged the dangers inherent in their desire to be America’s chief executive, and certainly there have been a handful who, here and there, established checks against their own influence, rather than doing everything they could to tip the balance in their favor. But how many have fervently identified with Shakespeare’s fallen Scotsman? How many have felt their bones ache with the worry that a few rash hours could pervert them from freedom’s champion into its destroyer?

Such was the uncommon spur to democracy that Lincoln located in Shakespeare’s play. And that was not all he found. For Macbeth was more than a negative example to the Kentucky-born president. It was also—as he meditated on that August day in 1863, with cannon shaking Fort Sumter and battalions of blue and gray rotting in thin-soiled graves from coasts to plains—an inspiration.

The first point of inspiration was the remarkable behavior of Macduff.

Macduff arrives onstage as a cliché: the tyrant killer. In a typical sixteenth or seventeenth-century drama, the tyrant killer is swung down (deus ex machina style) at the end—like Richmond in the closing moments of Shakespeare’s Richard III—to toss off a platitudinous sermon about virtuous kingship. Yet few of us in the audience pay that oration much serious notice, for occupying our fascination is the far more remarkable exhibition of the tyrant’s swaggering crimes: drowning siblings in barrels of wine, love-making at funerals, pursuing incestuous unions with underage nieces (to pluck a few examples from Richard III). Against the prodigious backdrop of such depravity, the tyrant killer is no more, really, than a convenient plot device, a way to efficiently resolve the magnetic spectacle of gonzo misbehavior that has captured our rapt attention across five acts. A way, that is, to get our delicious theater-villain and to eat him too.

Macduff defies this formulaic convention. He is not merely a dramatic tool for dispensing with Macbeth; he is himself a marvel, given perhaps the most extraordinary line in a play crammed with them. The line occurs after Macduff is warned by the thane of Ross that his ears are about to hear “the heaviest sound.” Macduff has an inkling of what the sound will be: “Hum. I guess at it.” But even so, he is not prepared. Ross reveals, “Your castle is surprised; your wife and babes savagely slaughtered.” Prompting Macduff to crack in dismay: “All my pretty ones? Did you say all?”

At this point, the future king Malcolm intercedes to counsel Macduff: “Dispute it like a man.” To which Macduff astonishingly rejoins: “I shall do so; but I must also feel it as a man.”

Feel it as a man. There is the extraordinary line. And it is extraordinary for two reasons. First, it is backtalk to a king—and not just any king. The rightful king. It is a calling into question how authoritative even the most credentialed of political authorities are. Second, it is a rejection of millennia of conventional machismo. Against that manly tradition, Macduff insists that true virility is not denying or discounting grief; it is owning it.

With this iconoclastic tenderheartedness, Macduff inverts Macbeth. Macbeth’s chase of the crown is premised on a disavowal of life’s inconvenient feelings; convinced that kindness is weakness, he hardens his mind to move without pity. And so ruthless does he manage to become that when his beloved wife perishes, he brushes off the news with a stoicism that blurs into nihilism:

Out, out, brief candle!

Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

By thinking this way, Macbeth means to make himself invulnerable. Yet, he does the opposite. His cold rigidity of purpose is not, he discovers in his last terrible moments, the path to eternal dynasty. Instead, its inflexibility engenders brittleness. Rendering Macbeth into the proverbial oak in the storm, it leaves him unable to bend or adapt; as a tempest of popular discontent builds against him in the play’s last scenes, he can only root himself, unyielding, against change’s roaring winds. Until, in sound and fury, he breaks.

Macduff exposes the flip side of Macbeth’s tragic epiphany: to acknowledge that you can be affected by life’s knocks is to learn that you can handle the mightiest shock. You can endure tragedy not by running from it but by bearing candid witness—and discovering resilience.

This discovery of resilience-through-vulnerability, as Lincoln would learn during his White House years, is vital for democracy. Democracy can never promise what Shakespearean kings (whether sincere, scheming, or simply rote) pledge at their coronations: steadfast harmony. Democracy is always volatile and conflicted, because it is many. The public does not all want one thing; the public wants a multitude, for the public is itself a multitude, filled with divergent appetites and longings. So it is that even the best democracies are continually skirmishing with themselves. And so it is that impatience with such upheaval has historically been the most frequent argument for autocracy. All the way back to Plato’s Republic (and all the way forward to the computer Singularity), the monarchists have insisted: If you want peace and stability, you need a single, rational ruler—not a mob of emotional voters.

Macduff counters that insistence by revealing that bodies wracked with passionate confusion can outdo logical regents. And at the bloody height of the US Civil War, when the young democracy’s body politic had literally split itself apart, the Scotsman provided a galvanizing example for America’s sorrow-laden leader. In Macduff’s defiant feeling, Lincoln could see that he did not have to close himself to the horrors around. He could admit that his country was cracked in half. He could acknowledge the calamity engulfing his fellow citizens. And by remaining open to that heartbreak, he could hold onto the rest of his emotional humanity: his empathy, his hope, his kindness.

Then there is the play’s second point of inspiration, more astonishing perhaps than the first. It is: the Weird Sisters.

What are the Weird Sisters? It’s impossible, ultimately, to say. We can, of course, try to define the Sisters. We can call them fates or witches or what-have-you, placing them in a tidily prefabricated mythological box. But within the play itself, they are a permanent mystery—earthly yet unearthly, as Macbeth’s friend and lieutenant Banquo succinctly puts it. They are, in other words, like the riddles—the day fair yet foul, the battle lost and won—that singsong from their skinny, bearded lips. But with one difference: where the riddles are solved, the Sisters themselves are never. What they are, where they come from, how they know: none of it is explained. They just are—and then are gone, abruptly vanished from the final climax that they have helped to brew.

In the end, all we can really say about the Sisters is that they make us believe, as they make Macbeth believe, in a future simultaneously confounding and affirming; grim and uplifting; absurd and beautiful and everything. Or, to put it more in the manner of Lincoln’s thoughts on that hot August day, all we can really say is that the Sisters are spiritual kin to American democracy: evocatively multifarious, riven with contradictions and strange illogics which nevertheless conjure our faith in a tomorrow that we strive, struggle, and sacrifice to make real.

A tomorrow that grapples in hope and anguish, ignorance and wisdom, with the irresolvable paradoxes of worldly polities. A tomorrow in which the Gettysburg dead—those who fought for slavery, and those who fought against it, and those who fought regardless—could be remembered together for consecrating a “nation conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” A tomorrow of our human worst and best mixed up in one cauldron, where supremacy is fragile—and catastrophe the kindling of its contrary.

Angus Fletcher (PhD, Yale)

Professor of Story Science at Ohio State’s Project Narrative and most recently the author of Wonderworks: Literary Invention and the Science of Stories (Simon & Schuster, 2021).

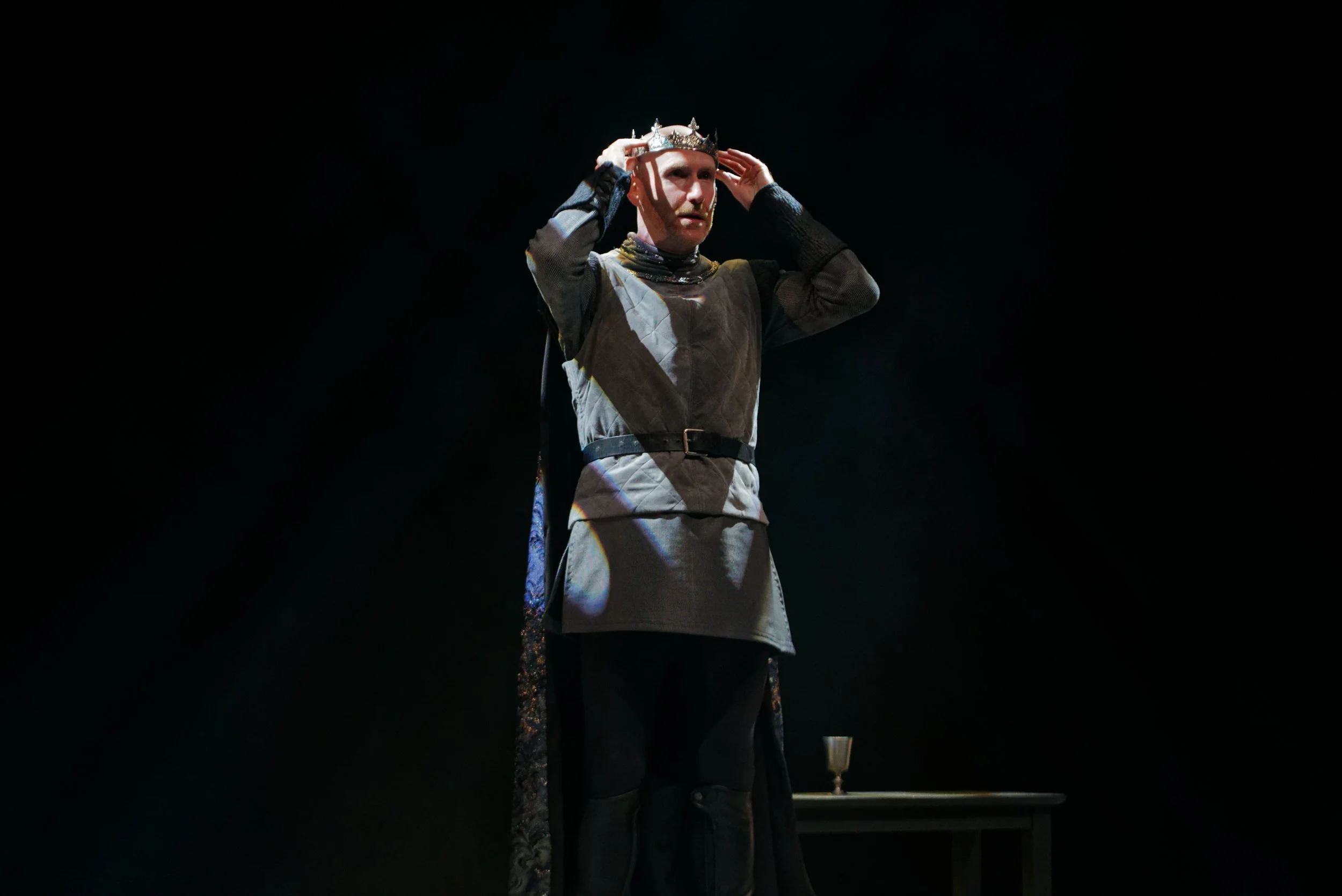

James Lavender in Aquila Theatre’s Macbeth, directed by Desiree Sanchez. Photo by Darryl Estrine.

Aamira Challenger (L) James Lavender (R) and in Aquila Theatre’s Macbeth, directed by Desiree Sanchez. Photo by Darryl Estrine.

Joshua Liburd (L) and Austin Lewis (R) in Aquila Theatre’s Macbeth, directed by Desiree Sanchez. Photo by Darryl Estrine.

James Lavender (L) and Aamira Challenger in Aquila Theatre’s Macbeth, directed by Desiree Sanchez. Photo by Darryl Estrine.

James Lavender (L) and Austin Lewis (R) in Aquila Theatre’s Macbeth, directed by Desiree Sanchez. Photo by Darryl Estrine.

Joshua Liburd (L) and Austin Lewis (R) in Aquila Theatre’s Macbeth, directed by Desiree Sanchez. Photo by Darryl Estrine.

Palmyra Mattner in Aquila Theatre’s Macbeth, directed by Desiree Sanchez. Photo by Darryl Estrine.

James Lavender and Ensemble in Aquila Theatre’s Macbeth, directed by Desiree Sanchez. Photo by Darryl Estrine.

Skye Pagon (L) and Palmyra Mattner in Aquila Theatre’s Macbeth, directed by Desiree Sanchez. Photo by Darryl Estrine.

Austin Lewis in Aquila Theatre’s Macbeth, directed by Desiree Sanchez. Photo by Darryl Estrine.

James Lavender in Aquila Theatre’s Macbeth, directed by Desiree Sanchez. Photo by Darryl Estrine.

Aamira Challenger in Aquila Theatre’s Macbeth, directed by Desiree Sanchez. Photo by Darryl Estrine.

James Lavender and Ensemble in Aquila Theatre’s Macbeth, directed by Desiree Sanchez. Photo by Darryl Estrine.

For more info on Aquila Theatre’s production of Macbeth visit aquilatheatre.com